CUDA tutorial: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (61 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<languages /> | |||

<translate> | |||

<!--T:37--> | |||

[[Category:Software]] | [[Category:Software]] | ||

=Introduction= | |||

This tutorial introduces the | =Introduction= <!--T:1--> | ||

This tutorial introduces the graphics processing unit (GPU) as a massively parallel computing device; the [[CUDA]] parallel programming language; and some of the CUDA numerical libraries for high performance computing. | |||

{{Prerequisites | {{Prerequisites | ||

|title= | |title=Prerequisites | ||

|content= | |content= | ||

This tutorial uses CUDA to accelerate C or C++ code: a working knowledge of one of these languages is therefore required to gain the most benefit. Even though Fortran is also supported by CUDA, for the purpose of this tutorial we only cover CUDA C/C++. From here on, we use term '''CUDA C''' to refer to CUDA C/C++. CUDA C is essentially a C/C++ that allows one to execute functions on both GPUs and CPUs. | |||

}} | }} | ||

{{Objectives | {{Objectives | ||

|title= | |title=Learning objectives | ||

Learning objectives | |||

|content= | |content= | ||

* Understand the architecture of a GPU | |||

* Understand the workflow of a CUDA program | |||

* | * Manage and understand the various types of GPU memories | ||

* | * Write and compile an example of CUDA code | ||

* | |||

* | |||

}} | }} | ||

=What is GPU ?= | =What is a GPU?= | ||

GPU, or | A GPU, or graphics processing unit, is a single-chip processor that performs rapid mathematical calculations for the purpose of rendering images. | ||

In the recent years however, such capability has been harnessed more broadly to accelerate computational workloads in cutting-edge scientific research. | |||

=What is CUDA ?= | |||

=What is CUDA?= <!--T:23--> | |||

CUDA stands for ''compute unified device architecture''. It is a scalable parallel programming model and software environment for parallel computing which provides access to instructions and memory of massively parallel elements in GPUs. | |||

= | =GPU architecture = <!--T:24--> | ||

There two main components of the GPU: | There two main components of the GPU: | ||

* Global memory | * Global memory | ||

** Similar to CPU memory | ** Similar to CPU memory | ||

** Accessible by both | ** Accessible by both CPUs and GPUs | ||

*Streaming multiprocessors (SMs) | *Streaming multiprocessors (SMs) | ||

** Each SM consists or many streaming processors (SPs) | ** Each SM consists or many streaming processors (SPs) | ||

**They perform actual computations | **They perform actual computations | ||

**Each SM has its own control | **Each SM has its own control unit, registers, execution pipelines, etc. | ||

= | |||

Before we start talking about programming model, let | =Programming model= <!--T:27--> | ||

Before we start talking about the programming model, let's go over some useful terminology: | |||

*Host – The CPU and its memory (host memory) | *Host – The CPU and its memory (host memory) | ||

*Device – The GPU and its memory (device memory) | *Device – The GPU and its memory (device memory) | ||

<!--T:25--> | |||

The CUDA programming model is a heterogeneous model in which both the CPU and GPU are used. | The CUDA programming model is a heterogeneous model in which both the CPU and GPU are used. | ||

CUDA code is capable of managing memory of both CPU and GPU as well as executing GPU functions, called kernels. Such kernels are executed by many GPU threads in parallel. Here is | CUDA code is capable of managing memory of both the CPU and the GPU as well as executing GPU functions, called kernels. Such kernels are executed by many GPU threads in parallel. Here is a five step recipe for a typical CUDA code: | ||

* Declare and allocate both the | * Declare and allocate both the host and device memories | ||

* Initialize the | * Initialize the host memory | ||

* Transfer data from Host memory to | * Transfer data from Host memory to device memory | ||

* Execute GPU functions (kernels) | * Execute GPU functions (kernels) | ||

* Transfer data back to the | * Transfer data back to the host memory | ||

= | |||

Simple CUDA code executed on GPU is called | =Execution model= <!--T:2--> | ||

* How do you run a | Simple CUDA code executed on GPU is called a ''kernel''. There are several questions we may ask at this point: | ||

* How do you make such run massively parallel ? | * How do you run a kernel on a bunch of streaming multiprocessors (SMs)? | ||

* How do you make such kernel run in a massively parallel fashion? | |||

Here is the execution recipe that will answer the above questions: | Here is the execution recipe that will answer the above questions: | ||

* each GPU core (streaming processor) | * each GPU core (streaming processor) executes a sequential '''thread''', where a '''thread''' is a smallest set of instructions handled by the operating system's scheduler. | ||

* all GPU cores execute the kernel in a SIMT fashion (Single Instruction Multiple Threads) | * all GPU cores execute the kernel in a SIMT fashion (Single Instruction, Multiple Threads) | ||

Usually the following procedure is recommended when it comes to executing on GPU: | Usually the following procedure is recommended when it comes to executing on GPU: | ||

1. Copy input data from CPU memory to GPU memory | 1. Copy input data from CPU memory to GPU memory | ||

2. Load GPU program ( | 2. Load GPU program (kernel) and execute it | ||

3. Copy results from GPU memory back to CPU memory | 3. Copy results from GPU memory back to CPU memory | ||

= | = Block-threading model = <!--T:3--> | ||

<!--T:4--> | |||

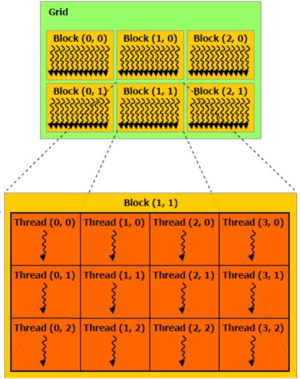

[[File:Cuda-threads-blocks.png|thumbnail|CUDA block-threading model where threads are organized into blocks while blocks are further organized into grid. ]] | [[File:Cuda-threads-blocks.png|thumbnail|CUDA block-threading model where threads are organized into blocks while blocks are further organized into grid. ]] | ||

Given a very large number of threads - in order to achieve massive parallelism one has to use all the threads possible - in a CUDA kernel, one needs to organize them somehow. In CUDA, all the threads are structured in threading blocks, the blocks are further organized into grids, as shown in the accompanying figure. In distributing the threads we must make sure that the following conditions are satisfied: | |||

* threads within a block cooperate via the shared memory | |||

* threads in different blocks can not cooperate | |||

In this model the threads within a block work on the same set of instructions (but perhaps with different data sets) and exchange data between each other via shared memory. Threads in other blocks do the same thing (see the figure). | |||

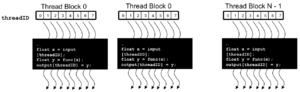

[[File:Cuda_threads.png|thumbnail|Threads within a block intercommunicate via shared memory. ]] | |||

<!--T:5--> | |||

Each thread uses IDs to decide what data to work on: | |||

* Block IDs: 1D or 2D (blockIdx.x, blockIdx.y) | |||

* Thread IDs: 1D, 2D, or 3D (threadIdx.x, threadIdx.y, threadIdx.z) | |||

Such a model simplifies memory addressing when processing multi-dimensional data. | |||

= | = Thread scheduling = <!--T:6--> | ||

Usually a streaming microprocessor (SM) executes one threading block at a time. The code is executed in groups of 32 threads (called warps). A hardware scheduller is free to assign blocks to any SM at any time. Furthermore, when an SM gets the block assigned to it, it does not mean that this particular block will be executed non-stop. In fact, the scheduler can postpone/suspend execution of such blocks under certain conditions when e.g. data becomes unavailable (indeed, it is quite time-consuming to read data from the global GPU memory). When it happens, the scheduler executes another threading block which is ready for execution. This is a so-called zero-overhead scheduling which makes the execution more streamlined so that SMs are not idle. | |||

= Types of GPU memories= <!--T:7--> | |||

There are several types of memories available for CUDA operations: | |||

* Global memory | |||

** off-chip, good for I/O, but relatively slow | |||

* Shared memory | |||

** on-chip, good for thread collaboration, very fast | |||

* Registers and Local Memory | |||

** thread work space , very fast | |||

* Constant memory | |||

= A few basic CUDA operations = <!--T:8--> | |||

== CUDA memory allocation == | |||

* cudaMalloc((void**)&array, size) | |||

** Allocates object in the device memory. Requires address of a pointer of allocated array and size. | |||

* cudaFree(array) | |||

** Deallocates object from the memory. Requires just a pointer to the array. | |||

== Data transfer == <!--T:9--> | |||

* cudaMemcpy(array_dest, array_orig, size, direction) | |||

** Copy the data from either device to host or host to device. Requires pointers to the arrays, size and the direction type (cudaMemcpyHostToDevice, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost, cudaMemcpyDeviceToDevice, etc.) | |||

* cudaMemcpyAsync | |||

** Same as cudaMemcpy, but transfers the data asynchronously which means it doesn't block the execution of other processes. | |||

= A simple CUDA C program= <!--T:10--> | |||

The following example shows how to add two numbers on the GPU using CUDA. Note that this is just an exercise, it's very simple, so don't expect to see any actual acceleration. | |||

</translate> | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang="cpp" line highlight="1,5"> | <syntaxhighlight lang="cpp" line highlight="1,5"> | ||

___global__ void add (int *a, int *b, int *c){ | |||

*c = *a + *b; | |||

} | |||

int main(void){ | int main(void){ | ||

int a, b, c; | |||

int *dev_a, *dev_b, *dev_c; | |||

int size = sizeof(int); | |||

// allocate device copies of a,b, c | // allocate device copies of a,b, c | ||

cudaMalloc ( (void**) &dev_a, size); | cudaMalloc ( (void**) &dev_a, size); | ||

cudaMalloc ( (void**) &dev_b, size); | cudaMalloc ( (void**) &dev_b, size); | ||

cudaMalloc ( (void**) &dev_c, size); | cudaMalloc ( (void**) &dev_c, size); | ||

a=2; b=7; | a=2; b=7; | ||

// copy inputs to device | // copy inputs to device | ||

cudaMemcpy (dev_a, &a, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice); | cudaMemcpy (dev_a, &a, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice); | ||

cudaMemcpy (dev_b, &b, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice); | cudaMemcpy (dev_b, &b, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice); | ||

// launch add() kernel on GPU, passing parameters | // launch add() kernel on GPU, passing parameters | ||

add <<< 1, 1 >>> (dev_a, dev_b, dev_c); | add <<< 1, 1 >>> (dev_a, dev_b, dev_c); | ||

// copy device result back to host | // copy device result back to host | ||

cudaMemcpy (&c, dev_c, size, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost); | cudaMemcpy (&c, dev_c, size, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost); | ||

cudaFree ( dev_a ); cudaFree ( dev_b ); cudaFree ( dev_c ); | cudaFree ( dev_a ); cudaFree ( dev_b ); cudaFree ( dev_c ); | ||

} | } | ||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

<translate> | |||

<!--T:17--> | |||

Are we missing anything ? | Are we missing anything ? | ||

That code does not look parallel ! | That code does not look parallel! | ||

Solution: | Solution: Let's look at what's inside the triple brackets in the kernel call and make some changes : | ||

</translate> | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang="cpp" line highlight="1,5"> | <syntaxhighlight lang="cpp" line highlight="1,5"> | ||

add <<< N, 1 >>> (dev_a, dev_b, dev_c); | add <<< N, 1 >>> (dev_a, dev_b, dev_c); | ||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

Here we replaced 1 by N, so that N different | <translate> | ||

<!--T:28--> | |||

Here we replaced 1 by N, so that N different CUDA blocks will be executed at the same time. However, in order to achieve parallelism we need to make some changes to the kernel as well: | |||

</translate> | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang="cpp" line highlight="1,5"> | <syntaxhighlight lang="cpp" line highlight="1,5"> | ||

__global__ void add (int *a, int *b, int *c){ | __global__ void add (int *a, int *b, int *c){ | ||

c[blockIdx.x] = a[blockIdx.x] + b[blockIdx.x]; | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

where blockIdx.x is the unique number identifying a | <translate> | ||

<!--T:29--> | |||

where blockIdx.x is the unique number identifying a CUDA block. This way each CUDA block adds a value from a[ ] to b[ ]. | |||

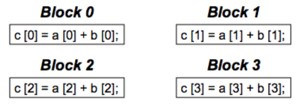

[[File:Cuda-blocks-parallel.png|thumbnail|CUDA blocks-based parallelism. ]] | [[File:Cuda-blocks-parallel.png|thumbnail|CUDA blocks-based parallelism. ]] | ||

<!--T:19--> | |||

Can we again make some modifications in those triple brackets ? | Can we again make some modifications in those triple brackets ? | ||

</translate> | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang="cpp" line highlight="1,5"> | <syntaxhighlight lang="cpp" line highlight="1,5"> | ||

add <<< 1, '''N''' >>> (dev_a, dev_b, dev_c); | add <<< 1, '''N''' >>> (dev_a, dev_b, dev_c); | ||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

<translate> | |||

<!--T:30--> | |||

Now instead of blocks, the job is distributed across parallel threads. What is the advantage of having parallel threads ? Unlike blocks, threads can communicate between each other: in other words, we parallelize across multiple threads in the block when heavy communication is involved. The chunks of code that can run independently, i.e. with little or no communication, are distributed across parallel blocks. | |||

= | = Advantages of shared memory= <!--T:20--> | ||

So far all the memory transfers in the kernel have been done via the regular GPU (global) memory which is relatively slow. Often | So far all the memory transfers in the kernel have been done via the regular GPU (global) memory which is relatively slow. Often we have so many communications between the threads that the performance decreases significantly. In order to address this issue there exists another type of memory called '''shared memory''' which can be used to speed-up the memory operations between the threads. However the trick is that only the threads within a block can communicate. In order to demonstrate the usage of such shared memory we consider the dot product example where two vectors are multiplied together element by element and then summed. Below is the kernel: | ||

</translate> | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang="cpp" line highlight="1,5"> | |||

__global__ void dot(int *a, int *b, int *c){ | __global__ void dot(int *a, int *b, int *c){ | ||

int temp = a[threadIdx.x]*b[threadIdx.x]; | |||

} | } | ||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

After each thread | <translate> | ||

<!--T:31--> | |||

After each thread computes its portion, we need to add everything together: each thread has to share its data. However, the problem is that each copy of thread's temp variable is private. This can be resolved by the use of shared memory. Below is the kernel with the modifications to use shared memory: | |||

</translate> | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang="cpp" line highlight="1,4"> | <syntaxhighlight lang="cpp" line highlight="1,4"> | ||

#define N 512 | #define N 512 | ||

__global__ void dot(int *a, int *b, int *c){ | __global__ void dot(int *a, int *b, int *c){ | ||

__shared__ int temp[N]; | |||

temp[threadIdx.x] = a[threadIdx.x]*b[threadIdx.x]; | |||

__syncthreads(); | |||

if(threadIdx.x==0){ | |||

int sum; for(int i=0;i<N;i++) sum+= temp[i]; | |||

*c=sum; | |||

} | |||

} | } | ||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

= Basic | <translate> | ||

== Memory | |||

= Basic performance considerations = <!--T:26--> | |||

== Memory transfer == | |||

* PCI-e is extremely slow (4-6 GB/s) compared to both host and device memories | * PCI-e is extremely slow (4-6 GB/s) compared to both host and device memories | ||

* Minimize | * Minimize host-to-device and device-to-host memory copies | ||

* Keep data on the device as long as possible | |||

* Sometimes it is not effificient to make the host (CPU) do non-optimal jobs; executing it on the GPU may still be faster than copying to CPU, executing, and copying back | |||

* Use memcpy times to analyse the execution times | |||

== Bandwidth == <!--T:21--> | |||

* Always keep CUDA bandwidth limitations in mind when changing your code | |||

* Know the theoretical peak bandwidth of the various data links | |||

* Count bytes read/written and compare to the theoretical peak | |||

* Utilize the various memory spaces depending on the situation: global, shared, constant | |||

== Common GPU programming strategies == <!--T:22--> | |||

* Constant memory also resides in DRAM - much slower access than shared memory | |||

** BUT, it’s cached !!! | |||

** highly efficient access for read-only, broadcast | |||

* Carefully divide data acording to access patterns: | |||

** read-only: constant memory (very fast if in cache) | |||

** read/write within block: shared memory (very fast) | |||

** read/write within thread: registers (very fast) | |||

** read/write input/results: global memory (very slow) | |||

</translate> | |||

Latest revision as of 21:21, 5 March 2019

Introduction

This tutorial introduces the graphics processing unit (GPU) as a massively parallel computing device; the CUDA parallel programming language; and some of the CUDA numerical libraries for high performance computing.

This tutorial uses CUDA to accelerate C or C++ code: a working knowledge of one of these languages is therefore required to gain the most benefit. Even though Fortran is also supported by CUDA, for the purpose of this tutorial we only cover CUDA C/C++. From here on, we use term CUDA C to refer to CUDA C/C++. CUDA C is essentially a C/C++ that allows one to execute functions on both GPUs and CPUs.

- Understand the architecture of a GPU

- Understand the workflow of a CUDA program

- Manage and understand the various types of GPU memories

- Write and compile an example of CUDA code

What is a GPU?

A GPU, or graphics processing unit, is a single-chip processor that performs rapid mathematical calculations for the purpose of rendering images. In the recent years however, such capability has been harnessed more broadly to accelerate computational workloads in cutting-edge scientific research.

What is CUDA?

CUDA stands for compute unified device architecture. It is a scalable parallel programming model and software environment for parallel computing which provides access to instructions and memory of massively parallel elements in GPUs.

GPU architecture

There two main components of the GPU:

- Global memory

- Similar to CPU memory

- Accessible by both CPUs and GPUs

- Streaming multiprocessors (SMs)

- Each SM consists or many streaming processors (SPs)

- They perform actual computations

- Each SM has its own control unit, registers, execution pipelines, etc.

Programming model

Before we start talking about the programming model, let's go over some useful terminology:

- Host – The CPU and its memory (host memory)

- Device – The GPU and its memory (device memory)

The CUDA programming model is a heterogeneous model in which both the CPU and GPU are used. CUDA code is capable of managing memory of both the CPU and the GPU as well as executing GPU functions, called kernels. Such kernels are executed by many GPU threads in parallel. Here is a five step recipe for a typical CUDA code:

- Declare and allocate both the host and device memories

- Initialize the host memory

- Transfer data from Host memory to device memory

- Execute GPU functions (kernels)

- Transfer data back to the host memory

Execution model

Simple CUDA code executed on GPU is called a kernel. There are several questions we may ask at this point:

- How do you run a kernel on a bunch of streaming multiprocessors (SMs)?

- How do you make such kernel run in a massively parallel fashion?

Here is the execution recipe that will answer the above questions:

- each GPU core (streaming processor) executes a sequential thread, where a thread is a smallest set of instructions handled by the operating system's scheduler.

- all GPU cores execute the kernel in a SIMT fashion (Single Instruction, Multiple Threads)

Usually the following procedure is recommended when it comes to executing on GPU: 1. Copy input data from CPU memory to GPU memory 2. Load GPU program (kernel) and execute it 3. Copy results from GPU memory back to CPU memory

Block-threading model

Given a very large number of threads - in order to achieve massive parallelism one has to use all the threads possible - in a CUDA kernel, one needs to organize them somehow. In CUDA, all the threads are structured in threading blocks, the blocks are further organized into grids, as shown in the accompanying figure. In distributing the threads we must make sure that the following conditions are satisfied:

- threads within a block cooperate via the shared memory

- threads in different blocks can not cooperate

In this model the threads within a block work on the same set of instructions (but perhaps with different data sets) and exchange data between each other via shared memory. Threads in other blocks do the same thing (see the figure).

Each thread uses IDs to decide what data to work on:

- Block IDs: 1D or 2D (blockIdx.x, blockIdx.y)

- Thread IDs: 1D, 2D, or 3D (threadIdx.x, threadIdx.y, threadIdx.z)

Such a model simplifies memory addressing when processing multi-dimensional data.

Thread scheduling

Usually a streaming microprocessor (SM) executes one threading block at a time. The code is executed in groups of 32 threads (called warps). A hardware scheduller is free to assign blocks to any SM at any time. Furthermore, when an SM gets the block assigned to it, it does not mean that this particular block will be executed non-stop. In fact, the scheduler can postpone/suspend execution of such blocks under certain conditions when e.g. data becomes unavailable (indeed, it is quite time-consuming to read data from the global GPU memory). When it happens, the scheduler executes another threading block which is ready for execution. This is a so-called zero-overhead scheduling which makes the execution more streamlined so that SMs are not idle.

Types of GPU memories

There are several types of memories available for CUDA operations:

- Global memory

- off-chip, good for I/O, but relatively slow

- Shared memory

- on-chip, good for thread collaboration, very fast

- Registers and Local Memory

- thread work space , very fast

- Constant memory

A few basic CUDA operations

CUDA memory allocation

- cudaMalloc((void**)&array, size)

- Allocates object in the device memory. Requires address of a pointer of allocated array and size.

- cudaFree(array)

- Deallocates object from the memory. Requires just a pointer to the array.

Data transfer

- cudaMemcpy(array_dest, array_orig, size, direction)

- Copy the data from either device to host or host to device. Requires pointers to the arrays, size and the direction type (cudaMemcpyHostToDevice, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost, cudaMemcpyDeviceToDevice, etc.)

- cudaMemcpyAsync

- Same as cudaMemcpy, but transfers the data asynchronously which means it doesn't block the execution of other processes.

A simple CUDA C program

The following example shows how to add two numbers on the GPU using CUDA. Note that this is just an exercise, it's very simple, so don't expect to see any actual acceleration.

___global__ void add (int *a, int *b, int *c){

*c = *a + *b;

}

int main(void){

int a, b, c;

int *dev_a, *dev_b, *dev_c;

int size = sizeof(int);

// allocate device copies of a,b, c

cudaMalloc ( (void**) &dev_a, size);

cudaMalloc ( (void**) &dev_b, size);

cudaMalloc ( (void**) &dev_c, size);

a=2; b=7;

// copy inputs to device

cudaMemcpy (dev_a, &a, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

cudaMemcpy (dev_b, &b, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

// launch add() kernel on GPU, passing parameters

add <<< 1, 1 >>> (dev_a, dev_b, dev_c);

// copy device result back to host

cudaMemcpy (&c, dev_c, size, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

cudaFree ( dev_a ); cudaFree ( dev_b ); cudaFree ( dev_c );

}

Are we missing anything ? That code does not look parallel! Solution: Let's look at what's inside the triple brackets in the kernel call and make some changes :

add <<< N, 1 >>> (dev_a, dev_b, dev_c);

Here we replaced 1 by N, so that N different CUDA blocks will be executed at the same time. However, in order to achieve parallelism we need to make some changes to the kernel as well:

__global__ void add (int *a, int *b, int *c){

c[blockIdx.x] = a[blockIdx.x] + b[blockIdx.x];

where blockIdx.x is the unique number identifying a CUDA block. This way each CUDA block adds a value from a[ ] to b[ ].

Can we again make some modifications in those triple brackets ?

add <<< 1, '''N''' >>> (dev_a, dev_b, dev_c);

Now instead of blocks, the job is distributed across parallel threads. What is the advantage of having parallel threads ? Unlike blocks, threads can communicate between each other: in other words, we parallelize across multiple threads in the block when heavy communication is involved. The chunks of code that can run independently, i.e. with little or no communication, are distributed across parallel blocks.

So far all the memory transfers in the kernel have been done via the regular GPU (global) memory which is relatively slow. Often we have so many communications between the threads that the performance decreases significantly. In order to address this issue there exists another type of memory called shared memory which can be used to speed-up the memory operations between the threads. However the trick is that only the threads within a block can communicate. In order to demonstrate the usage of such shared memory we consider the dot product example where two vectors are multiplied together element by element and then summed. Below is the kernel:

__global__ void dot(int *a, int *b, int *c){

int temp = a[threadIdx.x]*b[threadIdx.x];

}

After each thread computes its portion, we need to add everything together: each thread has to share its data. However, the problem is that each copy of thread's temp variable is private. This can be resolved by the use of shared memory. Below is the kernel with the modifications to use shared memory:

#define N 512

__global__ void dot(int *a, int *b, int *c){

__shared__ int temp[N];

temp[threadIdx.x] = a[threadIdx.x]*b[threadIdx.x];

__syncthreads();

if(threadIdx.x==0){

int sum; for(int i=0;i<N;i++) sum+= temp[i];

*c=sum;

}

}

Basic performance considerations

Memory transfer

- PCI-e is extremely slow (4-6 GB/s) compared to both host and device memories

- Minimize host-to-device and device-to-host memory copies

- Keep data on the device as long as possible

- Sometimes it is not effificient to make the host (CPU) do non-optimal jobs; executing it on the GPU may still be faster than copying to CPU, executing, and copying back

- Use memcpy times to analyse the execution times

Bandwidth

- Always keep CUDA bandwidth limitations in mind when changing your code

- Know the theoretical peak bandwidth of the various data links

- Count bytes read/written and compare to the theoretical peak

- Utilize the various memory spaces depending on the situation: global, shared, constant

Common GPU programming strategies

- Constant memory also resides in DRAM - much slower access than shared memory

- BUT, it’s cached !!!

- highly efficient access for read-only, broadcast

- Carefully divide data acording to access patterns:

- read-only: constant memory (very fast if in cache)

- read/write within block: shared memory (very fast)

- read/write within thread: registers (very fast)

- read/write input/results: global memory (very slow)