OpenACC Tutorial - Optimizing loops

- Understand the various levels of parallelism on a GPU

- Understand compiler messages telling how parallelization was performed.

- Learn how to get optimization advices out of the visual profiler

- Learn how to tell the compiler what parameters to user for parallelization.

Being smarter than the compiler

So far, the compiler did a pretty good job. We obtained a gain of about 3 in performance in the previous steps, compared to the CPU performance. It is now time to look more closely at how the compiler parallelized our code and see if we can give it some tips. In order to do so, we will need to understand the different levels of parallelism that can be used in OpenACC, and more specifically with an NVidia GPU. But first, lets look at some compiler feedback that we got while compiling the latest version (in steps2.kernels).

[name@server ~]$ pgc++ -fast -ta=tesla,lineinfo -Minfo=all,intensity,ccff -c -o main.o main.cpp

...

initialize_vector(vector &, double):

...

42, Intensity = 0.0

Loop is parallelizable

Accelerator kernel generated

Generating Tesla code

42, #pragma acc loop gang, vector(128) /* blockIdx.x threadIdx.x */

dot(const vector &, const vector &):

...

29, Intensity = 1.00

Loop is parallelizable

Accelerator kernel generated

Generating Tesla code

29, #pragma acc loop gang, vector(128) /* blockIdx.x threadIdx.x */

30, Sum reduction generated for sum

waxpby(double, const vector &, double, const vector &, const vector &):

...

44, Intensity = 1.00

Loop is parallelizable

Accelerator kernel generated

Generating Tesla code

44, #pragma acc loop gang, vector(128) /* blockIdx.x threadIdx.x */

Note that each loop is parallelized using vector(128). This means that the compiler generated instructions for chunk of data of length 128. This is where the programmer has an advantage over the compiler. Indeed, if you look in the file matrix.h, you will see that each row of the matrix has 27 elements. This means that the compiler generated instructions which waste computation on 101 elements. We will see how to fix that below.

Levels of parallelism OpenACC

There are three levels of parallelism that can be used in OpenACC. They are called vector, worker, and gang.

- vector threads perform a single operation on multiple data (SIMD) in a single step. If there are fewer data than the length of the vector, the operation is still performed on null values and the result is discarded.

- A worker computes one vector

- A gang comprises of one or multiple workers. All workers within a gang can share resources, such as cache memory or processor.

Multiple gangs run completely independently.

Because OpenACC is meant as a language for generic accelerators, there is no direct mapping to CUDA's threads, blocks and warps. Version 2.0 of the standard only states that gang must be the outermost level of parallelism, while vector must be the innermost level. The mapping is actually left to the compiler. However, while knowing there may be exceptions, you can think of the following mapping to be applicable:

- OpenACC vector => CUDA threads

- OpenACC worker => CUDA warps

- OpenACC gang => CUDA thread blocks

OpenACC clauses to control parallelism

The loop can be used with specific clauses to control the level of parallelism that the compiler should use to parallelize the next loop. The following clauses can be used:

- gang will apply gang-level parallelism to the loop

- worker will apply worker-level parallelism to the loop

- vector will apply vector-level parallelism to the loop

- seq will run the loop sequentially, without parallelism

Multiple of these clauses can be applied to a given loop, but they must be specified in a top-down order (gang first, vector last).

Specifying the type of device the clause applies to

Since different accelerators may perform differently depending on how the parallelization is done, OpenACC provides a clause to specify which type of accelerators the following clause applies to. This clause is called device_type. For example, the clauses device_type(nvidia) vector would apply vector parallelism to the loop only if the code is compiled for NVidia GPUs.

Specifying the size of each level of parallelism

Each of the vector, worker and gang clauses can take a parameter to explicitly states the their size. For example, the clause worker(32) vector(32) would create 32 workers to perform computations on vectors of size 32.

Accelerators may have limitations on how many vector, worker and gang a loop can be parallelized on. For NVidia GPUs for example, the following limitations apply:

- vector length must be a multiple of 32 (up to 1024)

- gang size is given by the number of workers times the size of a vector. This number cannot be larger than 1024.

Controlling vector length

Going back to our example, remember that we noticed the vector length was set to 128 by the compiler. Since we know that our rows contain 27 elements, we can reduce the vector length to 32. With a kernels directive, this is done with the following code:

#pragma acc kernels present(row_offsets,cols,Acoefs,xcoefs,ycoefs)

{

for(int i=0;i<num_rows;i++) {

double sum=0;

int row_start=row_offsets[i];

int row_end=row_offsets[i+1];

#pragma acc loop device_type(nvidia) vector(32)

for(int j=row_start;j<row_end;j++) {

unsigned int Acol=cols[j];

double Acoef=Acoefs[j];

double xcoef=xcoefs[Acol];

sum+=Acoef*xcoef;

}

ycoefs[i]=sum;

}

}

If you prefer the parallel loop directive, the vector length is specified at the level of the top loop with the vector_length clause. The vector clause is then used to specify to parallelize an inner loop over vector. The example becomes:

#pragma acc parallel loop present(row_offsets,cols,Acoefs,xcoefs,ycoefs) \

device_type(nvidia) vector_length(32)

for(int i=0;i<num_rows;i++) {

double sum=0;

int row_start=row_offsets[i];

int row_end=row_offsets[i+1];

#pragma acc loop reduction(+:sum) \

device_type(nvidia) vector

for(int j=row_start;j<row_end;j++) {

unsigned int Acol=cols[j];

double Acoef=Acoefs[j];

double xcoef=xcoefs[Acol];

sum+=Acoef*xcoef;

}

ycoefs[i]=sum;

}

If you actually make this change, you will see that, on a K20, the run time actually goes up, from about 10 seconds to about 15 seconds. This is because the compiler is doing something clever.

Guided analysis with the NVidia Visual Profiler

As instructed in the third section of this tutorial, open the NVidia Visual Profiler and start a new session with the latest executable we have built. Then, follow the following steps (see beside for screenshots of each step):

- Go in in the "Analysis" tab, and click on "Examine GPU Usage". Once the analysis is run, the profiler gives you a series of warning. This gives you indications on what it might be possible to improve upon.

- Then click on "Examine Individual Kernels". This will show you a list of kernels.

- Select the top one, and click on "Perform Kernel Analysis". The profiler will show you a more detailed analysis of this specific kernel, highlighting the most likely bottleneck. In this case, the performance is limited by memory latency.

- Click on "Perform Latency Analysis"

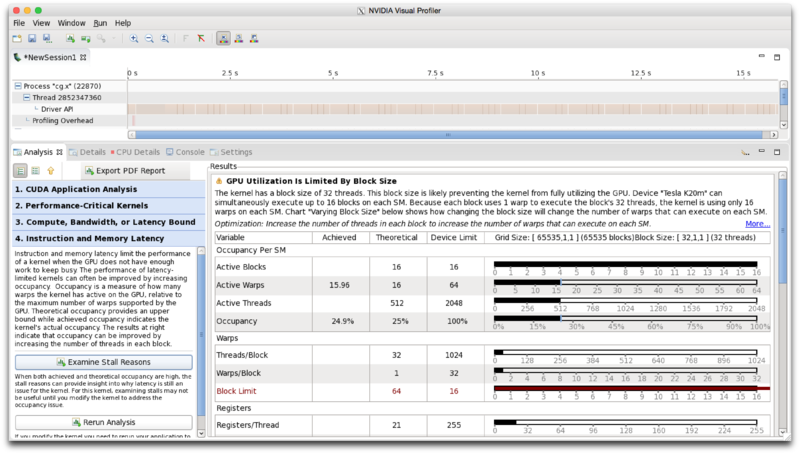

Once you have performed those steps, you should have the following information displayed.

This screenshot gives us a number of important information. First, the text tells us clearly that the performance is limited by the size of the blocks, which in OpenACC corresponds to the size of the gangs. Second, the "Active Threads" line tells us that the GPU is running 512 threads, while it could be running 2048. The occupancy line correspondingly states that the GPU is only used at 25% of its capacity. Occupancy is the ratio of how much the GPU is utilized over how much the GPU could be utilized. Note that 100% occupancy does not necessarily yield the best performance. However, 25% is quite low.

This screenshot gives us a number of important information. First, the text tells us clearly that the performance is limited by the size of the blocks, which in OpenACC corresponds to the size of the gangs. Second, the "Active Threads" line tells us that the GPU is running 512 threads, while it could be running 2048. The occupancy line correspondingly states that the GPU is only used at 25% of its capacity. Occupancy is the ratio of how much the GPU is utilized over how much the GPU could be utilized. Note that 100% occupancy does not necessarily yield the best performance. However, 25% is quite low.

The most important answers comes from the "Warps" table. This table tells us that the GPU is running 32 threads per block (OpenACC: vector threads per gang) while it could be running 1024. It also tells us that it is running 1 warp per block (OpenACC: worker per gang), while it could be running 32. Finally, the last line tells us that in order to fill the device, we would need to run 64 gangs, but the device can only hold 16. The conclusion to draw is that we need bigger gangs. We can do this by adding more workers while keeping the vector size to 32.

Adding more workers

Since we know that on NVidia GPUs, the maximum size of a gang is 1024, and is given by the size of the vector times the number of workers, we want to have 32 worker per gang. Using the kernels directive, this is done with the following code:

#pragma acc kernels present(row_offsets,cols,Acoefs,xcoefs,ycoefs)

{

#pragma acc loop device_type(nvidia) gang worker(32)

for(int i=0;i<num_rows;i++) {

double sum=0;

int row_start=row_offsets[i];

int row_end=row_offsets[i+1];

#pragma acc loop device_type(nvidia) vector(32)

for(int j=row_start;j<row_end;j++) {

unsigned int Acol=cols[j];

double Acoef=Acoefs[j];

double xcoef=xcoefs[Acol];

sum+=Acoef*xcoef;

}

ycoefs[i]=sum;

}

}

Note that we parallelize the outer loop on workers, since the inner loop is already using the vector level of parallelism.

Correspondingly, giving this information to the compiler with the parallel loop directive is done with the following code:

#pragma acc parallel loop present(row_offsets,cols,Acoefs,xcoefs,ycoefs) \

device_type(nvidia) vector_length(32) \

gang worker num_workers(32)

for(int i=0;i<num_rows;i++) {

double sum=0;

int row_start=row_offsets[i];

int row_end=row_offsets[i+1];

#pragma acc loop reduction(+:sum) \

device_type(nvidia) vector

for(int j=row_start;j<row_end;j++) {

unsigned int Acol=cols[j];

double Acoef=Acoefs[j];

double xcoef=xcoefs[Acol];

sum+=Acoef*xcoef;

}

ycoefs[i]=sum;

}

Doing this additional step gave us a gain of performance of a factor of almost two compared to what the compiler did by itself. The code ran in roughly 10 seconds on a K20 before and now runs in about 6 seconds.

Other optimization clauses

There are two clauses which we did not use in the examples, and which may be useful in optimizing loops. The first one is the collapse(N) clause. This clause is applied to a loop directive, and will cause the next N loops to be collapsed into a single, flattened loop. This is useful if you have many nested loops or when you have really short loops. The second clause is the tile(N,[M,...]) clause. This will break the next loops into tiles before parallelizing, and it can be useful if your algorithm has high locality because the device can then use data from nearby tiles.

Bonus exercise

The bonus folder contains a code which solves the Laplace Equation using the Jacobi method. Use what you have learned in this tutorial to port it to GPU using OpenACC and see what performance gain you are able to get.